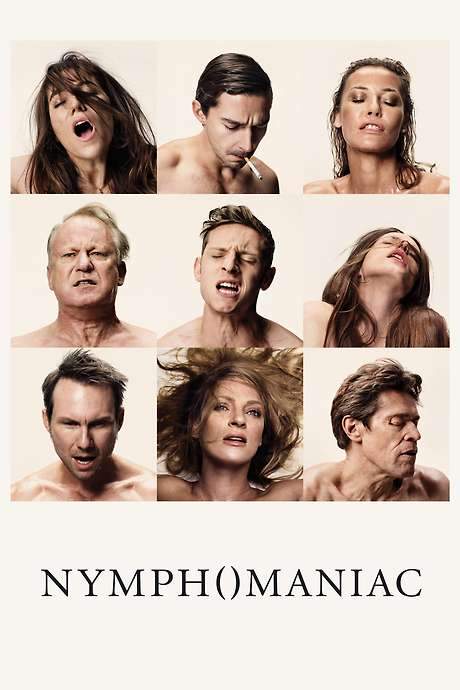

Nymphomaniac 2014

Directed by

Lars von Trier

Made by

Zentropa Entertainments

Test your knowledge of Nymphomaniac with our quiz!

Nymphomaniac Plot Summary

Read the complete plot summary and ending explained for Nymphomaniac (2014). From turning points to emotional moments, uncover what really happened and why it matters.

The film opens in a shadowy, rain-drenched quiet where a relentless mechanical thump fills the darkness. What seems to be a roadside ritual is actually the sound of machinery hammered by downpours, leading to a quiet, unsettling image—a motionless hand resting on a pavement. A distant, almost soothing wind and rain give way to a surge of heavy metal on the soundtrack as we enter a living space where a man—Stellan Skarsgård—wraps a scarf around his neck and steps into the world outside. He buys bait at a tackle shop, returns home, and stumbles upon a battered, unconscious woman on the ground. The woman is Charlotte Gainsbourg and she is badly beaten. He rouses her, promises to fetch help, but she resists, insisting that if he calls an ambulance or the police she will leave before he can return. He notes her injuries, offers tea, and, against her wishes, invites her inside.

In the dim light of the room, their uneasy truce begins. He suggests washing her clothes; she protests, asking him not to wash the coat. He asks what happened; she speaks of her own culpability—“it’s my fault because I’m a bad human being”—and she slowly opens up, revealing a need to talk about it. He invites her to tell her story, and she accedes, noticing a fly caught on a wall-mounted fishhook and using it as a narrative touchstone. He speaks of fly-fishing as a metaphor: the fly is light, the line heavy, and the lure must be matched to the fish’s hunger. She asks about his own fishing, and he admits he doesn’t catch much anymore. He shares a childhood memory from a “Complete Angler” book—romantic, almost sacred to him—before inviting her to begin at the start of her own story.

In this telling, the film pivots into a dramatic, multi-layered confession. The woman recounts her earliest experiences and how she discovers the “bait” in the adult world. The story pivots to a painful, intimate history: a two-year-old girl discovering her body, a young girl with a mother who is distant, and a father who shapes the child’s imagination with stories and science. The man listens, interjecting with gentle questions, while the woman traces how a sense of sin—taken not as a doctrine but as a personal burden—shapes her view of herself. In her telling, she makes it clear that she did not claim all of humanity to be sinful; she speaks of her own temptations and the way in which she has learned to read the world through the lens of longing and consequence.

As the story unfolds, the child grows into a girl who absorbs stories from her father, a doctor whose tales enchant her even as they hint at danger. The father’s stories about the ash tree—its beauty and its winter-dark buds—become a recurring motif that the woman recalls with a blend of affection and estrangement. The present-day man notes that the fly on the wall is called a nymph, the larval stage of a greater creature, and he uses their discussion to pivot toward the idea of education—an education that is not formal but experiential, a way of understanding desire, power, and consequence.

The narrative then shifts to the character we come to know as Joe, the adult version of the girl, played by Stacy Martin. In this section, Joe is seen as she and her friend B—played by Sophie Kennedy Clark—embark on a journey that begins with a ritualized contest: who can seduce the most men on a train, in a bid to win a tangible prize. The two move through the compartments with a practiced, almost strategic ease—counting, calculating, and learning the rhythms of attraction. The storyteller notes the river’s changing currents, the way fish gather, tease, and bite; the metaphor becomes a map of human behavior: timing, visibility, and the art of choosing when to strike.

In this chapter, the film is unflinching about adult encounters, yet it remains careful about how it presents them. Joe’s early sexual awakenings unfold in a sequence of candid, but non-graphic, moments that establish the power she wields and the costs she pays. Among these memories is a pivotal first sexual encounter with a young man—an event that is later reframed in terms of the broader arc of her life. The train sequence also puts into relief Joe’s growing sense that desire can be both a tool and a burden, capable of untying knots and creating new ones. A key moment in this section is a conversation where a married man becomes entangled in a moment of shared risk and consequence, a moment that Joe later discusses with a calm, clinical clarity that juxtaposes against the storm of her feelings.

On the journey through memory, a number of figures emerge through the archive of Joe’s life. The adult Shia LaBeouf appears as Jerôme, a man from Joe’s past who begins as a quiet, uncomfortable, almost predatory presence but gradually becomes a focal point of longing and conflict. The transition from a respectful memory to a complicated attraction is rendered in a way that mixes humor and tension, and it is here that the film begins to widen its lens beyond mere sexual appetite toward questions of love, obligation, and memory. When Joe enters the office world, she encounters Jerôme again, this time in a professional setting where the power dynamics shift and the boundary between personal history and present day work becomes central to her experience. A tense elevator scene and a tour through Jerôme’s private space become symbolic waypoints in their evolving relationship.

The film’s frame narrative continues to host a meditation on love, attachment, and the price of desire. When Jerôme becomes a recurring figure in Joe’s life, the sense of history—how the past informs the present—reaches a new depth. A sequence in which Joe begins to explore her feelings more openly, even as she navigates power, control, and gendered expectations, shows how her identity is shaped by both the men who cross her path and the inner critics she has internalized. A later encounter in which Joe’s professional life intersects with her personal history—when she provocatively asserts her independence in the face of Jerôme’s assumed authority—highlights a turning point: the need to define herself not by the men she encounters but by the boundaries she sets and the autonomy she forges.

In a later chapter, Joe’s life becomes a mosaic of long relationships and more casual, combustible encounters, and the woman is forced to face the consequences of living with a life defined by hunger and repetition. The “Mrs. H” chapter centers on a complicated ménage with a woman who becomes a mirror for loss, memory, and the stubbornness of desire. Uma Thurman appears as Mrs. H, a wife who enters Joe’s life with a quiet, unnerving presence and leaves behind a cascade of emotional ripples that challenge Joe to confront what it means to destroy and to be destroyed in return. The scene with Mrs. H is less a showdown than a confrontation with the limits of control—how the past leaks into the present, and how the body can be both shelter and wound.

The narrative then shifts into a darker, more meditative register: Delirium. A stark, black-and-white sequence takes us into the hospital wards where Joe’s father, a doctor, is confronted with illness, fear, and the fragility of life. The sequence is intimate and harrowing, filled with intimate acts that aim to fill a void and an enduring sense of loneliness that lingers even after death. Christian Slater, who portrays Joe’s father, returns to the screen in these scenes, offering a counterpoint to Joe’s own self-fashioning. The doctor’s perspective—devoted, exhausted, resilient—frames Joe’s later reflections on mortality, guilt, and the complicated ways people cope with loss. The doctor’s bedside presence, the emotional tremor of delirium tremens, and the chasm between memory and reality all feed into Joe’s ongoing inquiry into who she is when she is most exposed.

Throughout these interwoven chapters, the film uses music as a living counterpoint to narrative. Seligman, a patient, piercing intellectual figure, introduces Joe to Bach and the concept of polyphony—the idea that multiple independent melodies can coexist harmoniously. He crafts a parallel between the polyphonic organ’s three voices and Joe’s own life: the bass of one lover, the melody of another, and a third voice that completes the relational chord. The conversation about a cantus firmus—an anchored melodic line—becomes a way to describe Joe’s own approach to love, memory, and the art of living with one’s desires. The film even places a bold, carefully staged quotation from their dialogue, inviting the viewer to consider poetry and mathematics as ways of understanding human behavior.

As the narrative reaches its fifth movement, Joe divides her life into three core relationships—the three voices that compose her “Little Organ School.” The bass, denoted by a man with a red car, is predictable, devoted, and patient, a steady rhythm that gives structure to her days. The second voice, a more predatory, Jaguar-like presence, tests boundaries and challenges her control. The third, a close confidant and partner, becomes a catalyst for a deeper, more intimate fusion—the moment when desire becomes a shared, almost sacred space. The parallel montage pairs Joe in her intimate scenes with the organ’s pedals and pipes, visually weaving sex, music, and memory into a single, complex fabric. The moment when Joe finally consummates a significant relationship with Jerôme is rendered as a climactic, multi-voiced sequence that culminates in a quiet, overwhelming vulnerability. The trio of lovers—F, Jerôme, and G—are represented in a three-way split-screen, mirroring the three voices on the organ, before the scene cuts away with a sense of suspended consequence.

The end of this installment sits at a raw, unresolved edge. Joe, exhausted and overwhelmed, confesses that she cannot feel the same intensity as before and asks for the possibility of feeling again. The confession is intimate, incomplete, and deeply human, ending on an open note: to be continued. The closing credits tease forthcoming glimpses of what lies ahead in Nymphomaniac: Vol. II, leaving the viewer with a dual pull of curiosity and unease about where Joe’s story will travel next.

Fill all my holes.

Love is blind. The erotic is about saying yes; love, in contrast, can distort or demand more than a person can bear.

Nymphomaniac Characters

Explore all characters from Nymphomaniac (2014). Get detailed profiles with their roles, arcs, and key relationships explained.

Joe (adult) – Charlotte Gainsbourg

The central narrator who frames her life’s sexual odyssey in conversation with Seligman. She oscillates between fearless exploration and emotional detachment, revealing how trauma and longing shape her choices. Her confessional reveals a complex blend of hunger, curiosity, and vulnerability as she searches for connection.

Seligman

An older observer who hosts Joe’s confession, offering philosophical reflections on memory, art, and happiness. He serves as a calm, clinical counterpoint—intelligent, perceptive, and sometimes unsettling—guiding the storytelling process.

Jerôme

Joe’s former lover and a catalyst in her life; a figure of authority and attraction who both draws Joe in and complicates her emotional landscape. He embodies the tension between desire and distance, shaping her later attitudes toward love and power.

Mrs. H

Uma Thurman’s character, the wife of a lover who confronts Joe with the consequences of infidelity. She represents a moral counterweight and a maternal presence that intensifies the emotional stakes of Joe’s actions.

B

Joe’s friend and fellow member of the youth club The Little Flock; she shares a rebellious stance toward conventional love and sexuality. B participates in the train-journey competition that underpins the film’s exploration of flirtation as sport.

Young Joe

The adolescent version of Joe, whose first sexual awakenings with a boy on a moped set the groundwork for her later relationship with desire. This period reveals the roots of her fearless yet fragile identity.

Nymphomaniac Settings

Learn where and when Nymphomaniac (2014) takes place. Explore the film’s settings, era, and how they shape the narrative.

Time period

Contemporary

The framing takes place in the present day, with Seligman guiding Joe’s confession. The story intercuts with extensive flashbacks spanning Joe’s childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood. This creates a multi-decade timeline that contrasts intimate domestic spaces with broader social environments.

Location

Seligman’s Private Home, Train (Intercity), Hospital, Ash Tree Forest by the Pond, Office/Printing House, Joe’s Apartment

The primary setting is a warmly cluttered private home where Seligman cares for Joe after she is found beaten. The narrative travels through crowded train compartments during Joe’s sexual odyssey, and to a hospital when trauma surfaces. Other key spaces include a quiet forest by a pond for reflective walks and the sterile spaces of an office and Joe’s apartment, highlighting Joe’s movement between isolation and social contact.

Nymphomaniac Themes

Discover the main themes in Nymphomaniac (2014). Analyze the deeper meanings, emotional layers, and social commentary behind the film.

🔥

Lust

Joe’s relentless sexual curiosity drives the plot, shaping her identity and relationships. The film treats desire as both liberating and destructive, challenging simple moral judgments. It presents erotic pursuit as a powerful force that can connect people or hollow them out. Pleasure is interrogated as a potential path to self-knowledge or self-destruction.

🎼

Memory

Memory functions as the scaffolding of Joe’s self-portrait, with Seligman probing its reliability as she recounts disparate life moments. Musical motifs and symbolic images structure memories into multiple voices, echoing Bach’s polyphony. Traumatic childhood moments and formative affairs shape present behaviors, while recollection becomes a method of self-analysis. The act of telling the story becomes a way to piece together identity.

🧭

Power

Power dynamics thread through Joe’s encounters, revealing how desire can become strategic and performative. The Little Flock and office episodes illustrate control, manipulation, and the pulled-between-roles nature of her relationships. The film questions whether power can exist without honesty and the moral costs of using others for pleasure. Joe’s agency collides with judgment, complicating her sense of self.

Coming soon on iOS and Android

The Plot Explained Mobile App

From blockbusters to hidden gems — dive into movie stories anytime, anywhere. Save your favorites, discover plots faster, and never miss a twist again.

Sign up to be the first to know when we launch. Your email stays private — always.

Nymphomaniac Spoiler-Free Summary

Discover the spoiler-free summary of Nymphomaniac (2014). Get a concise overview without any spoilers.

In a rain‑slick alley, a solitary man named Seligman discovers an unconscious woman lying on the pavement. He carries her to the modest safety of his home, offering tea, blankets, and a gentle curiosity about the strange wounds that mark her body. As the storm fades, the woman introduces herself simply as Joe, a self‑confessed nymphomaniac, and begins to unwind the tangled threads of a life lived in relentless pursuit of desire. Their evening unfolds as a dialogue that drifts from the raw intimacy of her recollections to the quiet meditations of Seligman’s own passions—fly‑fishing, the mathematics of the Fibonacci sequence, and the resonant chords of organ music—creating a spellbinding contrast between the bodily and the cerebral.

The film’s world hangs in a perpetual twilight of rain‑soaked streets and the warm, cluttered interior of Seligman’s house, where the hum of a distant organ intertwines with the soft patter of water outside. This setting becomes a stage for an unconventional confessional, where explicit honesty meets philosophical introspection, and where the ordinary—tea, a coat, a simple conversation—takes on a heightened, almost ritualistic significance. The tone oscillates between stark realism and lyrical abstraction, inviting the audience to question the boundaries between craving, love, and the search for meaning.

Joe’s narrative voice is unapologetically candid, revealing a pattern of experiences that she frames not merely as sexual conquest but as a means of mapping the contours of her own identity. Across the table, Seligman listens with a mixture of empathy and scholarly curiosity, offering observations that turn mundane details into metaphors for larger existential questions. The encounter becomes a dance of confession and contemplation, a study in how two strangers can become mirrors for each other’s hidden compulsions and quiet longings, all set against a backdrop that feels both intimate and unsettlingly vast.

Can’t find your movie? Request a summary here.

Featured on this page

What's After the Movie?

Not sure whether to stay after the credits? Find out!

Explore Our Movie Platform

New Movie Releases (2025)

Famous Movie Actors

Top Film Production Studios

Movie Plot Summaries & Endings

Major Movie Awards & Winners

Best Concert Films & Music Documentaries

Movie Collections and Curated Lists

© 2025 What's After the Movie. All rights reserved.