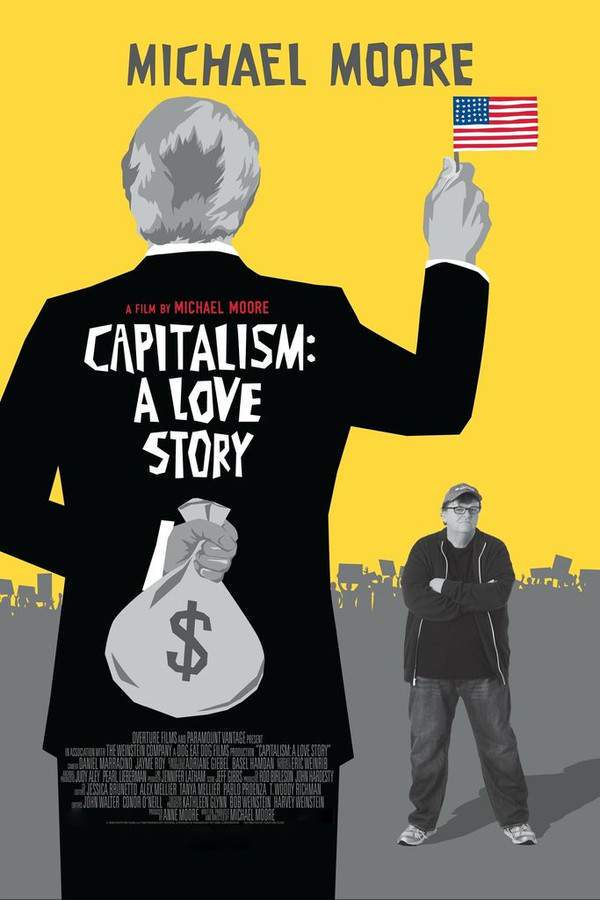

Capitalism: A Love Story 2009

Michael Moore’s documentary explores the detrimental effects of corporate greed and unchecked capitalism on American society. The film examines how prioritizing profits has impacted individuals and communities, from the American heartland to the financial institutions of Wall Street and the political landscape of Washington D.C. It reveals the human cost of a system where economic policies often overshadow the well-being of citizens.

Does Capitalism: A Love Story have end credit scenes?

No!

Capitalism: A Love Story does not have end credit scenes. You can leave when the credits roll.

Meet the Full Cast and Actors of Capitalism: A Love Story

Explore the complete cast of Capitalism: A Love Story, including both lead and supporting actors. Learn who plays each character, discover their past roles and achievements, and find out what makes this ensemble cast stand out in the world of film and television.

No actors found

External Links and Streaming Options

Discover where to watch Capitalism: A Love Story online, including streaming platforms, rental options, and official sources. Compare reviews, ratings, and in-depth movie information across sites like IMDb, TMDb, Wikipedia or Rotten Tomatoes.

Ratings and Reviews for Capitalism: A Love Story

See how Capitalism: A Love Story is rated across major platforms like IMDb, Metacritic, and TMDb. Compare audience scores and critic reviews to understand where Capitalism: A Love Story stands among top-rated movies in its genre.

61

Metascore

7.1

User Score

74%

TOMATOMETER

74%

User Score

7.4 /10

IMDb Rating

71

%

User Score

Take the Ultimate Capitalism: A Love Story Movie Quiz

Challenge your knowledge of Capitalism: A Love Story with this fun and interactive movie quiz. Test yourself on key plot points, iconic characters, hidden details, and memorable moments to see how well you really know the film.

Capitalism: A Love Story Quiz: Test your knowledge on Michael Moore's poignant critique of modern capitalism and its societal impacts in 'Capitalism: A Love Story'.

What song is featured during the bank robbery montages at the start of the film?

Louie, Louie

Hound Dog

Jailhouse Rock

Born to Run

Show hint

Awards & Nominations for Capitalism: A Love Story

Discover all the awards and nominations received by Capitalism: A Love Story, from Oscars to film festival honors. Learn how Capitalism: A Love Story and its cast and crew have been recognized by critics and the industry alike.

15th Critics' Choice Awards 2010

Best Documentary Feature

2009 Toronto International Film Festival Awards 2009

Full Plot Summary and Ending Explained for Capitalism: A Love Story

Read the complete plot summary of Capitalism: A Love Story, including all major events, twists, and the full ending explained in detail. Explore key characters, themes, hidden meanings, and everything you need to understand the story from beginning to end.

The film presents a compelling exploration of America’s socioeconomic landscape, intertwining biting social critiques with real-life accounts of those grappling with the fallout from the recent economic crisis. It opens with security footage of bank robberies, set to the tune of “Louie, Louie,” capturing the chaotic spirit of desperation. A juxtaposition is quickly made through an Encyclopedia Britannica archive video, allowing audiences to compare contemporary America with the fallen grandeur of the Roman Empire.

As the narrative unfolds, the audience is presented with poignant home videos depicting families facing eviction, alongside a glimpse into the world of the “Condo Vultures,” a Florida real estate agent who thrived amidst a backdrop of foreclosures. This transition leads to a reflection on a nostalgic era often depicted as the “golden days” of American capitalism post-World War II.

A significant moment occurs when the film showcases an excerpt from President Jimmy Carter’s “Malaise” speech, wherein he warns the nation about a looming “crisis of confidence.” As it progresses, we see the shift during the Reagan years in the 1980s; policies initiated by Don Regan dismantled many safeguards, allowing corporations to gain unprecedented clout while unions dwindled, and socioeconomic disparities widened.

The documentary dives into the Luzerne County court scandal, alongside powerful testimonies like that of Captain Sullenberger, who sheds light on the dismal treatment of airline pilots. It also highlights the disturbing revelation of “dead peasant insurance” policies that enabled companies to profit from employee deaths.

In a notable segment, Michael Moore engages with several Catholic priests, including Bishop Thomas Gumbleton, who voice their concerns regarding capitalism’s discord with Christianity’s teachings. He presents a satirical hypothetical in which Jesus, as a capitalist, would focus on “maximizing profits” and enforcing pay-for-service healthcare, juxtaposed against pundits who celebrate capitalist endeavors as divine blessings.

A leaked Citigroup memo emphasizes the stark reality of wealth concentration, revealing that the top 1% commands more financial resources than the bottom 95% combined. This alarming statistic raises questions about societal disparities and elicits commentary from Stephen Moore of the Wall Street Journal, who controversially claims that “capitalism is a lot more important than democracy.”

The film also ventures into alternative economic models like co-determination worker cooperatives, showcasing that democracy can thrive within business frameworks, challenging the conventional capitalist narrative.

Moore draws on Dr. Jonas Salk’s legacy, noting how he selflessly chose public good over profit. This prompts a profound question regarding the current generation’s draw towards high finance rather than scientific innovation. In his exploration, Moore makes an earnest attempt to decode Wall Street’s derivatives and credit default swaps but is met with vague explanations and cryptic responses, reinforcing his belief that the complexities serve only to obfuscate and allow wrongdoing.

The portrayal of Alan Greenspan and the U.S. Treasury’s pivotal roles leading to the housing bubble signals pivotal shifts in the American economic landscape. With first-hand accounts from a former employee at Countrywide Financial, the film uncovers how favorable mortgage programs benefited many Washington elites.

Discussions with William Black illuminate the precarious position of the economy, likening it to a dam on the verge of collapse. The series of events that led to the controversial 2008 bailout, championed by Hank Paulson, is meticulously laid out. As Moore engages members of Congress—most notably Marcy Kaptur, who frames the bailout as a “financial coup d’état”—the intensity of the situation becomes markedly pronounced.

A gripping moment occurs during Moore’s exchange with Elizabeth Warren, wherein he queries, “Where’s our money?” referring to the substantial bailout funds. Warren’s chilling response of “I don’t know,” follows a suspenseful pause that accentuates the level of accountability sought.

The film captures the excitement leading to the 2008 U.S. elections, contrasting the rhetoric of capitalism versus socialism as part of a broader political maneuver. Hope is momentarily found in Barack Obama’s potential to course-correct the nation. In a striking contrast, archival footage of Franklin D. Roosevelt advocating for a Second Bill of Rights powerfully underscores what could be in contrast to present-day policies.

Moore articulates his own spiritual conflict as a Catholic, pondering whether Jesus would engage in hedge funds or short selling. His conclusion burgeons from a deeper revelation, positing that one cannot claim both capitalism and Christianity without a fundamental contradiction in values.

Amidst the film’s heavier themes, we see bright spots represented by individuals like Elizabeth Warren, Warren Evans, and Marcy Kaptur, who advocate for responsible governance and community support. The conclusion sees Moore symbolically encircling banks with police lines, as he asserts that capitalism is an evil that must be supplanted by a just democratic system, beseeching like-minded individuals to “speed it up,” a nod to a past presidential exhortation.

Uncover the Details: Timeline, Characters, Themes, and Beyond!

Coming soon on iOS and Android

The Plot Explained Mobile App

From blockbusters to hidden gems — dive into movie stories anytime, anywhere. Save your favorites, discover plots faster, and never miss a twist again.

Sign up to be the first to know when we launch. Your email stays private — always.

Watch Trailers, Clips & Behind-the-Scenes for Capitalism: A Love Story

Watch official trailers, exclusive clips, cast interviews, and behind-the-scenes footage from Capitalism: A Love Story. Dive deeper into the making of the film, its standout moments, and key production insights.

Capitalism: A Love Story Themes and Keywords

Discover the central themes, ideas, and keywords that define the movie’s story, tone, and message. Analyze the film’s deeper meanings, genre influences, and recurring concepts.

Capitalism: A Love Story Other Names and Titles

Explore the various alternative titles, translations, and other names used for Capitalism: A Love Story across different regions and languages. Understand how the film is marketed and recognized worldwide.

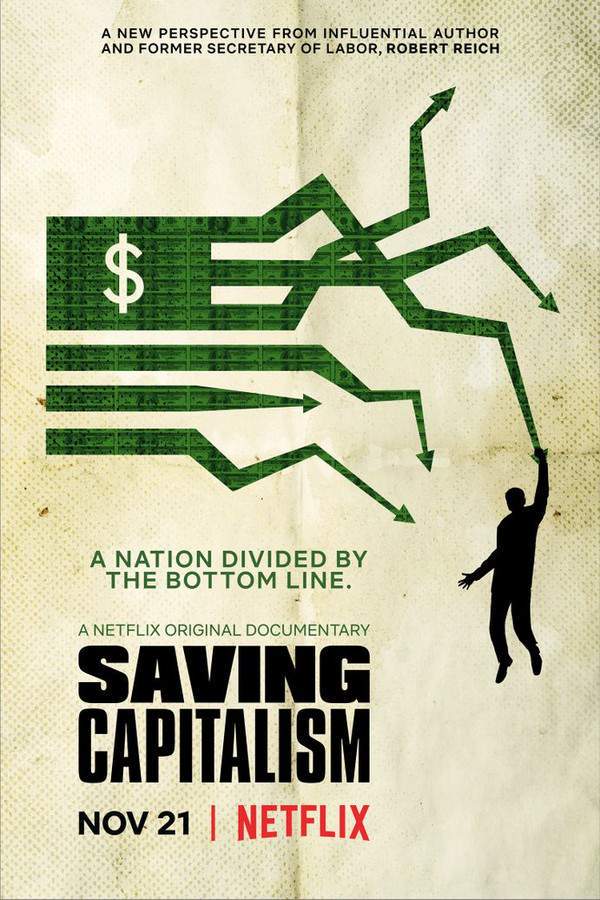

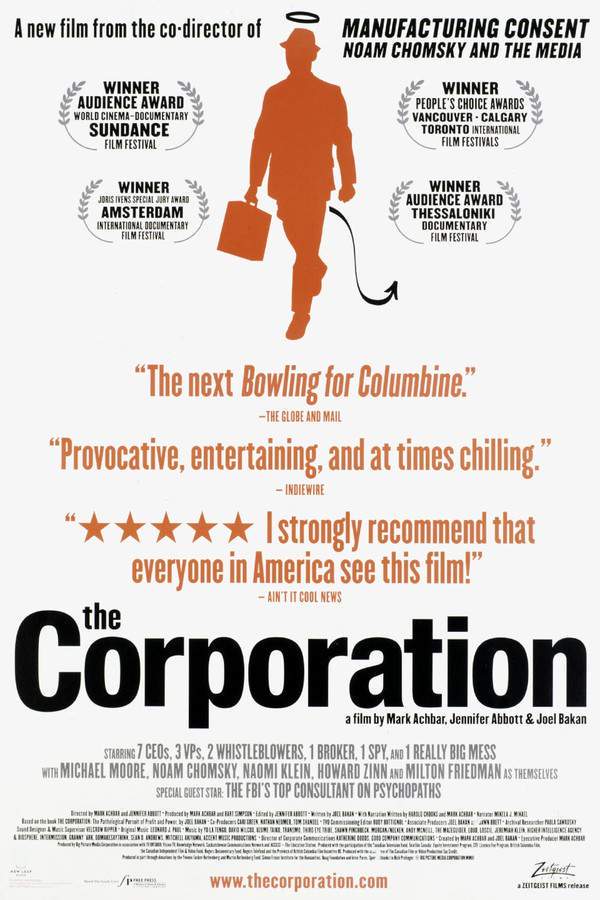

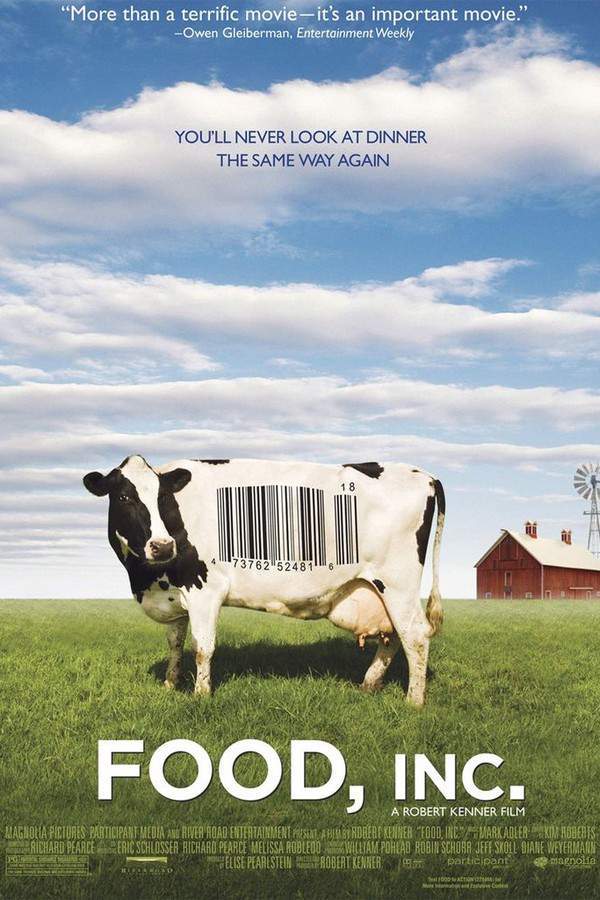

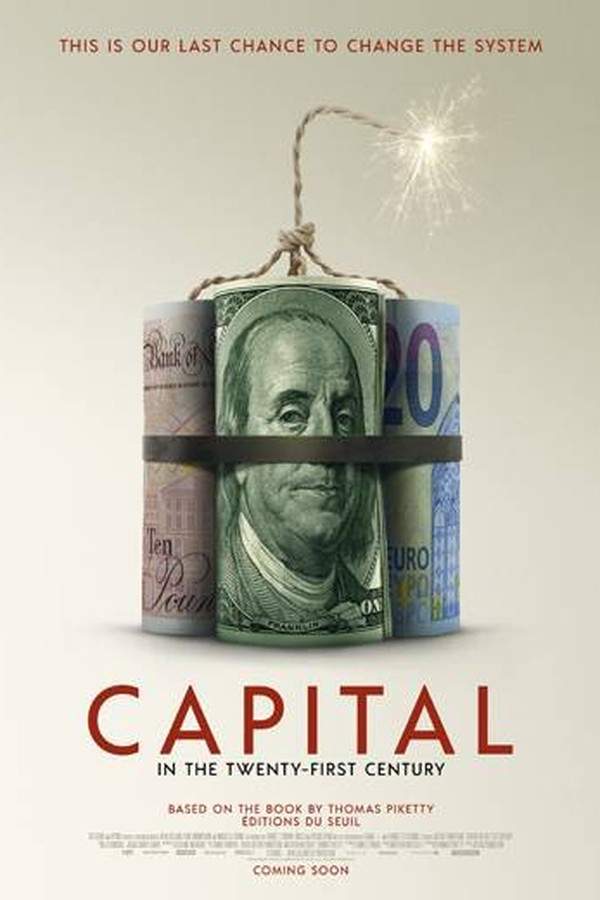

Similar Movies To Capitalism: A Love Story You Should Know About

Browse a curated list of movies similar in genre, tone, characters, or story structure. Discover new titles like the one you're watching, perfect for fans of related plots, vibes, or cinematic styles.

Quick Links: Summary, Cast, Ratings, More

What's After the Movie?

Not sure whether to stay after the credits? Find out!

Explore Our Movie Platform

New Movie Releases (2026)

Famous Movie Actors

Top Film Production Studios

Movie Plot Summaries & Endings

Major Movie Awards & Winners

Best Concert Films & Music Documentaries

Movie Collections and Curated Lists

© 2026 What's After the Movie. All rights reserved.